Butchers Row - Nos 14, 15, 16, 17

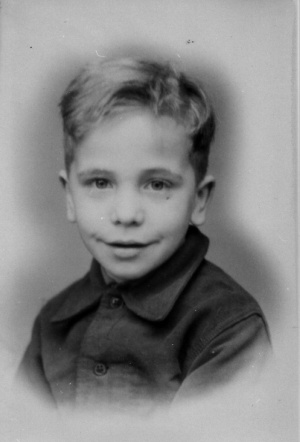

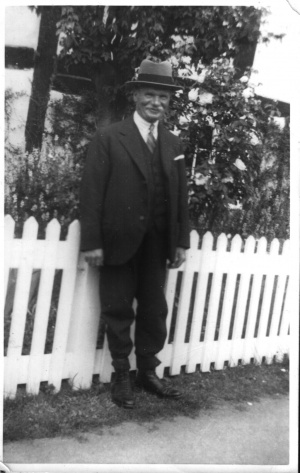

John Lee Radbourne

No. 17 housed all the Radbourne family, Bert, Ruth, Bill, Vic, Walter, Tom and Mary, and Vic doesn't know just how his Mum managed with all those children. But, despite the cramped conditions in their two-up-two-down cottage, they were very happy, spending summer days as toddlers playing on the millstone by the front door. Have a look next time you are passing No. 17, and see if that millstone is still there!

John Lee Radbourne, their Dad, was usually referred to as Old Jack Radbourne, to distinguish him from Young Jack Radbourne! Old Jack Radbourne worked at the mill, driving a wagon with three horses. So, when the millstone needed replacing, he brought the old one back to his house for a step by his front door.

Old Jack was one of the first members of the the Working Mens' Club when it opened and he was also a Church Choir member for over 50 years. Sometime in his life, he also became a Parish Councillor, and at one time, was elected District Councillor representing Clifford Parish Council on Marston Sicca Rural District Council.

When the Radbournes left No. 17 about 1924 and moved across the road to a detached cottage, No. 45, Fred Richardson moved in. He came from Preston, a bachelor at that time, living with his Mum, and he lived at No. 17 for a short while, before moving also across the road to No. 47.

Sold to the Village Charity

When Fred moved out, Mrs. Rouse moved in! When I arrived in the village in the mid 1960's her husband's funeral was still remembered well in the village, I suppose because he was a young man when he died, leaving two small children. The Rouses lived outside the village, and John Batsford's horse and wagon brought his coffin to the Church.

Mrs. Rouse was still living at No. 17 when I came to the village, though her two children Hilda, and Cyril had grown up and left home by then. My memory of her is the afternoon walks she used to take with Bert Gardener, usually finishing up at the seat by the War Memorial. They were so constantly together, that I thought they were husband and wife, until I got to know them.

She was tenant of No. 17, and when the then owner sold, the Trustees of our village charity bought the house to be used as an almshouse. The kitchen became part of the main living room, a hall led from the front door and up the stairs. A bathroom was put in what had originally been the back bedroom, and downstairs an extension was made which then became a large kitchen.

Mrs. Rouse loved the additions. “Oh,” she said to me looking round her large living room and large kitchen. “How I wish all this was here when I had my children. I had to work in such a small kitchen, and there never was enough room for the two children and me in the living room.. This is beautiful. A real home.”

From then on, there were a series of senior citizens who moved in, and on their death, more moved in – all loving the little cottage.

Kath Salmon

One was Kath Salmon who lived with her father Diggie Salmon at the bungalow which, at one time formed part of the Meeting Room at the end of The Nashes. Kath suffered from breathing problems probably after contacting TB. The bungalow was damp and her clothes were often mouldy if left too long without airing. It was the then Rector, when No. 17 became free, who suggested to The Charity that Kath move in. She did – and loved it there, going each Wednesday to Bingo, and always coming back a little merry. One night coming back to No 17 she slipped on some kerb stones that had been loosened by a tractor. She finished up in hospital, but refused to listen to her friends to sue whoever was responsible for not keeping the kerb stones firm. “No! I don't want to sue.” she declared crossly, but in her heart, she knew she was to blame. It was just that she was a little too merry that night to be able to concentrate on walking on the pavement instead of the kerb.

Her drinking sometimes caused her to sleep so heavily that she didn't wake up the next day until the early evening. Anxious neighbours seeing her milk-bottles outside in the sun, would call Avril (as her next of kin), but when Avril shouted up to her bedroom window several times, she would hear Kath's voice shouting hysterically, “Don't come in Avril. Don't come in!” Kath did not like anyone seeing her in a bad state after a night of alcohol. There was one time however, when there was no answer the whole of the day,, and the Police had to be called in the next morning, to force open the front door. Avril followed them in, and there was Kath sitting up in her bed and screaming out “No! No! No! Don't come in!”

Butchers Row Nos 16 and 15

Mrs. Mary Ann Cockbill lived at No. 16 with her twin daughters, Agnes and Gertrude. Records show that she and her husband Ewib, kept the dairy at No. 18 Clifford Chambers, before it was made into a home. Gertrude (I think usually called Lil) married Charles Giles, and became a war widow when her husband died in April 1918 aged 26. She was left with a small son, Derek.

Len Salmon brought his young bride Phyllis to this cottage when it became empty, and in that small two bedroom house, they managed to sleep their two girls and one boy until, at last Mrs. Rees-Mogg found room for them at No. 26 The Square. Lawrence was 9 when they moved to The Square, sleeping on a camp bed alongside his parents' bed. all through his life at No. 16

In No. 15 lived Mr. and Mrs. Jack Halstead who both worked the laundry for the Manor at the 'top' mill. Mr. Halstead always wore a type of game-keepers cap.

When they moved out, Mr. and Mrs. Percy Salmon moved in as newly-weds. Mrs. Percy Salmon as Miss Elizabeth Spencer (commonly called Betty or Bet) came to work at The Manor as housemaid, and later, when the Manor was being repaired after the fire, at The Lodge, where she found blacking the grates there, "the worst job in her whole life". Percy was working for The Manor as a groom, and the stables made a nice courting place for them.

They lived all the rest of their lives at No. 15 with their first son John arriving the following year of their marriage and Gerald arriving 13 months later. Because John did not walk until his little brother was several months old, Mrs. Salmon had to carry both boys in her arms upstairs and down, and they were very narrow and twisting stairs.

I remember seeing a handwriting book with John's name on it, and all the pages were taken up with one sentence written over and over again in neat copper-plated writing, "I promise I will not drink any intoxicating liquor". John was 6 when he wrote those sentences!! He was killed in Normandy in 1944 aged 19.

Percy died in early 1960. Gerald had married and left home by then, and Mrs. Salmon was on her own, though she was delighted by the birth of a little grandson Richard, and loved taking him for a walk in his pram when the family visited her. She always kept herself busy, making sure she cooked a good meal for herself each day - even on days when she felt unwell. She busied herself in her vegetable garden until it became too much for her. Her only delight then, was to visit her two friends, Miss Richardson (Fred's sister) and Mrs. Nason. In fact, the library van driver, as they walked to his van to change their books, used to refer to them as 'Last of the summer wine'!

Her death was very sudden and unexpected. She was found at the bottom of her steep cottage stairs one Boxing Day morning. But at the Inquest, it was reported that her death wasn't the result of the fall down the stairs, but a heart attack that caused her to fall.

Butcher's Row No. 14

No. 14 was the Butcher's shop. Meat was brought from Stratford in a wagon, and was driven into the back yard through double doors (where the garage is now), to be stored, but I don't quite know where it was stored. The present dining room at No. 14 was the actual shop, with meat hanging from the low beams. As this is now our dining room, I know just how low these beams are, so I would imagine customers must have banged their heads on the carcases as they came into the shop to be served.

Lawrence's grandad, Diggie Salmon, could just remember coming to this Butcher's shop when he was about 5. He was born in 1880. When meat could no longer be bought at No. 14, customers went to the village shop instead, who took on the meat-selling business to add to their usual stock. The shop at that time was kept by Jack Ward.

The Silvesters lived at No. 14, but they might have arrived when the butcher's shop closed. We have found the name Frank Silvester written in pencil on the trapdoor above our landing, leading to the rafters, but unfortunately with no date.

Mr. Francis John Silvester was the one I heard about when I arrived in the village. He worked at both mills. He and his wife had two sons, Leslie and Leonard. Leonard married Dolly Hastie from Manor Cottage, and many years later when she was a widow, we invited Dolly for a meal at No. 14. She told us that, during her early married years she lived with her parents-in-law, and our dining room (once the butcher's shop) was her living room.

As she stood and looked around the room that had once been her own home, she showed me the places in the outside wall where daylight had come through and she had had to plug the gaps with rags to keep the room warm.

When we arrived at No 14, we found quite a lot of alterations had been made by the previous owner, Mrs. Mann. who was tragically widowed when her youngest child, David was only a baby. She had an older child, Sheila, little more than a toddler at the time the children's father died in a motor-bike accident..

When Sheila married a welsh farmer, her mother went to live there, but she also spent time staying with her son, then a policeman living at Ilmington, and enjoyed grandchildren from both families. Sheila married soon after we married, so our move to Sheila's old home took place about three years later.

Lawrence's Dad could remember how the house used to be, as he often played with the Silvester boys. The present kitchen was originally the scullery, with copper. There was a bakehouse the other side of the kitchen wall, approached by a door from outside. Both copper and bakehouse shared the same, very tall, chimney; - though when the bakehouse was pulled down, its part of the chimney was also pulled down, and all that was left were quite a lot of blackened bricks. The remaining part of the chimney was definitely in need of pointing, though we didn't know that at the time.

We had had our electric oven placed in the kitchen to use in the summer. But in the place where the copper had been, was a Rayburn. I was thrilled when at last it was cool enough to light it and cook with it. As you can guess, fumes were noticed straight away in the kitchen; not too bad, until a north-east wind blew. And then the fumes were terrible.

I coughed and coughed while I cooked, pleading with my little daughter to play with her baby brother in the living room so I could shut her out of the kitchen. I had to tie a silk scarf round the bottom part of my face for protection - and that is how I cooked all winter. Was I glad when the warm weather came, and I could resort to the electric cooker! But we needed the Rayburn on during the winter, because it warmed up the rest of the house if I left the kitchen door open.

The back door was right opposite the front door, and the wind, when it was strong, blew in through the one door and out to the other, via all the other doors opening into the hall; the wind howling with delight while we shivered. When, two years later we started doing alterations, that chimney came down; the Rayburn went out. Both cupboards either side of the Rayburn were removed, and in the place of one, was set a new back door with windows, and in place of the other, a window. So we finished up with a kitchen full of light - and WARM! And our old back door was sold to someone dealing with old things, who gave us £5 for it on account of the ancient large key and lock. In its place was an attractive window looking out to the view down to the river.

In the back garden near our new back door, was a very lethal bush which practically pricked you just by looking at it! Its thin brittle branches each bearing vicious weapons seemed to reach out to you as you passed it. I mentioned it once to Mrs. Reece who said that it sounded just the bush she needed in her garden to keep the cats out! She sent her husband, Alec Reece (parents of Angela Wylam) to dig it out. He came armed with spade and overalls. "Mr. Reece," I declared when I saw him, "You need to wear armour to deal with this thing!"

But he dealt with it in his overalls, telling me it was known as 'Butchers Broom'; took it home and planted it to stop the cats - and then it died! But it gave me a picture of how our living room was swept when it was covered in the sawdust every butcher's shop had in those days.

Tragedy at No. 14

The rest of the Salmon family were born there - James on the day we moved. William came along 15 months later – and that was our family. Lawrence had said that when James was born! !! William was definitely a little God-planned baby.

Just 3 months after his second birthday when he was beginning to talk in short sentences and roar with laughter over everything, he caught a virus one Monday and developed breathing problems.. It took three urgent phone calls before the Doctor came out. In desperation Avril telephoned Miss Taylor at No. 29 (retired from her work as Assistant Matron at Birmingham Accident), and when she arrived, she helped them make a tent over William's cot. The kettle was brought up from downstairs and was constantly kept boiling with the steam going into the 'tent' where Avril sat cuddling William. His breathing was terrible now, gasping for breath, the sound coming out from his throat . But this constant boiling of the kettle kept fusing the lights, and Lawrence constantly had to dash downstairs to the fuse box to put it right. By 6.00am Miss Taylor said, “That is enough. I am going to ring the Doctor!”

Her voice was heard by Lawrence and Avril, “This child is very very ill. You must come NOW!” but it was another two hours before he came. Once there, an ambulance was ordered and soon Avril and William were being driven to Warwick Hospital. Even though very ill, William who loved travelling in cars, wanted to sit up, and with me holding an oxygen mask to his face (which William kept trying to push away) he had to look at all the traffic passing by.

In the hospital he was immediately put in an oxygen tent with a window looking into her the Sister's office. His breathing became worse, and this time Avril noticed that his stomach was caving in almost to the back of his spine as he attempted to get breath to breath. By the afternoon, she noticed that his head was slipping back as he lay exhausted on the bed. Every two minutes a Nurse was coming in to take his temperature, and when she came in, Avril drew her attention to this. Immediately, she rapped on the window, and almost immediately the Paediatrician, Sister and other Nurses appeared. The french windows to this room were thrown open. The oxygen tent was whipped off. Avril was told afterwards that William was having convulsions.

Slowly William came round as the Paediatrician called his name. Avril from the bottom of the bed also called him, telling him that his Crackerjack was here (William's favourite cuddly toy that he took to bed with him each night.) The staff made way for Avril to come to William's side. She held Crackerjack to William and told William that Crackerjack wanted a cuddle. But William looked at her, his eyes so grey in his white face, that was so bright blue around his mouth - but she could see that he didn't know her. Then there was a rattle, coming from his mouth – and he was gone.

The emergency team came with the trolley within a few seconds, the Paediatrician having rung the bell above William's head. Avril, longing to do something for her little boy and knowing she couldn't- but everyone else could - , could not stay and watch anymore. She rushed out of the room crying, and was taken by a Nurse to a special room. The Matron was called and soon a phone call went to Lawrence who, with very little sleep the night before, had gone off to work.

It was a long time before he arrived. The hospital, although telling him to come to the hospital, didn't tell him how urgent it was, and Lawrence, with all the dirt and sweat over his face, felt he couldn't go to Hospital until he had had a bath and changed into clean clothes.

We were both taken into Intensive Care where William lay under a ventilator. His honey-coloured hair which had become so wet under the oxygen-tent, now had dried and turned into a golden halo of tight curls. For the rest of that day and the next three days, neither the Paediatrician or the physiotherapists never left the hospital. Every two hours the physiotherapists came and pummelled away at William's chest, to break up the mucus in his breathing tubes so it could be sucked up. But by Wednesday late afternoon, they had to come before the two-hours were up, as the sticky mucus had built up to such an extent, that William had stopped breathing – and his heart had stopped.

Again and again the mucus would be sucked up and his heart start again, but by this time the Paediatrician was giving us warning of brain damage. The virus has been identified on the Tuesday as haemopholis influenza - a type of meningitis, and it was known as a 24 hour killer of children two years and under. William was two years and three months old, and because he had survived over those 24 hours, the Paediatrician had hopes that he would be the one two-year old to survive.

But William's body with its strong heart and strong lungs, became weaker and weaker and at 4.00pm on Friday 1st August 1980, he died.

The whole village went into shock and the Church was packed at the funeral with the villagers, with just two pews saved for the relatives. It was a beautiful service with the Rector talking about William's loud 'Amens' after everyone else had said their Amen at services. And his need to scramble up onto the pew when the organ started and sing. with an open hymn book in his hands, looking at the congregation behind him. And his face at the window at No. 14 where he would say 'Low' to everyone as they passed by.

Lawrence and Avril had such spiritual help from many friends, and healing came to Avril a few months after William's death when, listening to a tape given by David Pawson, she was able to say, “Lord God, if I could see ahead as You can see; if I knew what You know – then I would have done, with William, what You have done.”

Tom, their fourth child and third son arrived a year later, a week before Prince Charles and Princess Di's wedding. Henry arrived 15 months later. The children grew up at No. 14 going to local schools; went to respective Universities throughout the years; found work; married, and Lawrence and Avril are now left with a three bedroomed house, a study, kitchen, dining room and living room and bathroom – and a very large garden. All very empty and quiet now, and very hard work to keep tidy and free of weeds.